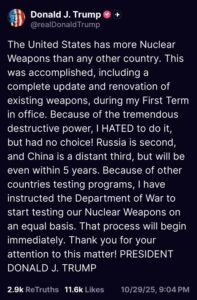

In forty-eight hours that mattered, two signals landed against the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) norm. First, at the UN General Assembly’s First Committee, the United States voted against the annual CTBT resolution while India abstained, per the official vote board displayed in the room on 31 October 2025 (formal UN documentation typically posts with delay). Second, prior to the voting on UN resolution, President Trump signalled through his Truth Social account that he had instructed the Pentagon to start testing U.S. nuclear weapons. The same week, NATO ran its Steadfast Noon nuclear-sharing drill, and U.S. Strategic Command opened Global Thunder 26, its annual nuclear command-and-control exercise. Earlier, Russia had tested Poseidon unmanned underwater vehicle and unmatched 9M730 Burevestnik nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed cruisle missile, clarifying that these cannot be regarded as nuclear tests in any way. Together, these moves thin the political canopy above a norm that remains scientifically robust and verifiably monitored.

In forty-eight hours that mattered, two signals landed against the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) norm. First, at the UN General Assembly’s First Committee, the United States voted against the annual CTBT resolution while India abstained, per the official vote board displayed in the room on 31 October 2025 (formal UN documentation typically posts with delay). Second, prior to the voting on UN resolution, President Trump signalled through his Truth Social account that he had instructed the Pentagon to start testing U.S. nuclear weapons. The same week, NATO ran its Steadfast Noon nuclear-sharing drill, and U.S. Strategic Command opened Global Thunder 26, its annual nuclear command-and-control exercise. Earlier, Russia had tested Poseidon unmanned underwater vehicle and unmatched 9M730 Burevestnik nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed cruisle missile, clarifying that these cannot be regarded as nuclear tests in any way. Together, these moves thin the political canopy above a norm that remains scientifically robust and verifiably monitored.

The CTBT is near-universal non-proliferation treaty that seeks placing a qualitative cap on development and testing of nuclear weapons. It has 187 signatories and 178 ratifications as of 2025. Yet the treaty cannot enter into force until all Annex-2 states ratify (the treaty’s list of 44 designated states whose ratification is legally required for entry into force); several have not, which include the United States (signed, not ratified), China, India, Pakistan, Israel, Iran, and Egypt; Russia’s revocation of CTBT ratification in 2023 mirrored the situation in the U.S. Against that backdrop, a U.S. No and an Indian abstention are not just optics; they are permissive signals that normalize option-keeping on explosive testing.

The CTBT is near-universal non-proliferation treaty that seeks placing a qualitative cap on development and testing of nuclear weapons. It has 187 signatories and 178 ratifications as of 2025. Yet the treaty cannot enter into force until all Annex-2 states ratify (the treaty’s list of 44 designated states whose ratification is legally required for entry into force); several have not, which include the United States (signed, not ratified), China, India, Pakistan, Israel, Iran, and Egypt; Russia’s revocation of CTBT ratification in 2023 mirrored the situation in the U.S. Against that backdrop, a U.S. No and an Indian abstention are not just optics; they are permissive signals that normalize option-keeping on explosive testing.

The statement to restart testing injected strategic ambiguity about whether “testing” meant explosive underground shots or non-nuclear experiments and delivery-system trials. American and European media coverage underscored that officials did not clarify whether underground nuclear-explosive tests were in scope. That ambiguity, by itself, lowers the activation energy for others to move from talk to preparations. The CTBTO’s Executive Secretary, Robert Floyd, warned the same day that any explosive test “would be harmful and destabilizing” and that the International Monitoring System (IMS)/ International Data Centre (IDC) network stands ready to detect violations.

NATO’s annual Steadfast Noon ran 13–24 October 2025 and was flagged publicly by Allied Command Operations (ACO) and Global Thunder 26 opened on 21 October. Russia, in the same window, touted a new flight of the Burevestnik, claimed duration ~15 hours / flew for 14,000 km, subsequently discussed in open reporting, with Norway’s intelligence service publicly confirming a launch from Novaya Zemlya. Regardless of technical debates, the timing thickened the global signal economy around nuclear forces.

On the science and verification side, the CTBT still rests on an unusually solid foundation: a global, 300+ station IMS/IDC network with proven detection and forensic capability. Politically, however, the canopy is thinning. The U.S. never ratified the CTBT; Russia de-ratified in 2023 to restore symmetry with Washington; and several Annex-2 states never signed. The net effect is that even in the absence of explosions, high-profile political acts like a lone No, an abstention, or a presidential order re-legitimate preparation for the resumption of nuclear weapons testing. That is the phase where cascades begin.

Three decades of the U.S. Stockpile Stewardship Program sustain high confidence without explosive yield by using non-nuclear explosives without creating a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. Subcritical experiments at the Nevada National Security Site’s underground PULSE/U1a complex, the forthcoming Scorpius radiography machine, and advanced multi-physics codes underwrite safety, reliability, and life-extension work without crossing criticality.

Independent assessments and officials emphasize that reconstituting underground explosive testing would take years, not weeks. Some estimates converge around ~36 months under current conditions, which seem underplaying the capabilities. In parallel, the U.S. is rebuilding plutonium pit production at Los Alamos and Savannah River, albeit with schedule delays and cost risks flagged by Government Accountability Office. The marginal technical gain from an explosive test is thus small; the diplomatic and normative cost is large. The U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) is under a military and legal requirement to achieve a capacity of no fewer than eighty pits per year at Los Alamos and fifty at Savannah. A plutonium pit is a hollow plutonium sphere, typically the size of a bowling ball, which is the primary stage of a nuclear weapon. Plutonium is compressed by high explosives in the pit to create a nuclear fission chain reaction.

India has never signed the CTBT. Since 1998 it has observed a voluntary moratorium while arguing the treaty is discriminatory absent broader disarmament. An elite-level dispute persists over the thermonuclear device India tested in 1998, through public claims by K. Santhanam that the shot “fizzled,” echoed by former AEC chair P. K. Iyengar; the government publicly rebutted these claims, but the epistemic split endures. Placed alongside a U.S. vote against entry into force of the CTBT, India’s abstention reads as option-maintenance, preserving manoeuvre space to revisit thermonuclear validation if others move first. In South Asia’s action-reaction ladder, that is non-benign.

Cascades rarely begin with a plutonium pit of shaft firing. They begin with politics: a high-profile post, a conspicuous vote, an exercise announcement. Next comes preparation: new vertical shafts or horizontal drifts, stepped-up subcritical cadence, diagnostic upgrades, which are moves that are legal under a unilateral moratorium but lower time-to-test. Finally, a demonstration shot. In the week of 13-31 October 2025, each rung was visible: NATO and USSTRATCOM signalled readiness; Russia advertised Burevestnik; the U.S. voted “No” and floated “resumption” of testing. That is a classic signal-stack and a recipe for misperception under compressed timelines.

The testing taboo sits within a wider arms-control order that has eroded over two decades. The United States withdrew from the ABM Treaty in 2002, the INF Treaty ended in 2019, the U.S. exited Open Skies in 2020 and Russia followed, New START survives only as a shell, extended to 2026 with Russia suspending participation in 2023 while indicating numerical limits would be observed for now. The cumulative message: rules and inspections have yielded to signals, which is exactly the environment in which testing talk is most dangerous.

| Treaty | Scope | Verification | Current status (2025) |

| ABM Treaty (1972) | Limits national missile defense | National technical means; data exchanges | U.S. withdrawal effective 2002. (White House archive) |

| INF (1987) | Bans ground-launched ballistic & cruise missiles 500–5,500 km | On-site inspections | Terminated 2019. (Arms Control Association) |

| Open Skies (1992) | Cooperative observation flights | Aircraft/sensor inspections | U.S. withdrawal 2020; Russia withdrawal 2021. (State Dept.) |

| New START (2010) | Strategic delivery/warhead limits | On-site inspections; data exchanges | Extended to 2026; Russia suspended participation in 2023. (Arms Control Today) |

| CTBT (1996) | Prohibits all nuclear explosive tests | Global IMS/IDC network | 187 signatories; 178 ratifications; U.S. not ratified; Russia de-ratified 2023. (CTBTO) (Reuters) |

If the common goal is to keep options without collapsing the norm, the answer is to raise the reputational cost of preparations and to insulate verification from politics. Three feasible steps could be useful among the contending parties.

One – Reaffirm zero-yield in writing. Annual, public letters by nuclear-armed states, including non-parties like the U.S. and India, lodged with the CTBTO on fixed dates.

Two – Excavation transparency. A 90-day prior notice before new vertical shafts or horizontal drifts at historical test sites like Pokhran, NNSS, Lop Nur, Semipalatinsk, Novaya Zemlya).

Three – Observer windows for sub-critical tests. Voluntary CTBTO / technical observer access to selected PULSE/U1a subcritical setups and post-shot data notes to demonstrate zero-yield discipline.

Washington could pair stewardship investments (Scorpius, subcritical cadence) with a public pledge that no explosive testing will occur absent a declared, extraordinary technical finding judged unsolvable by stewardship, acknowledging GAO’s oversight on program management and pit production risk.

Likewise, ifstrategic credibility is New Delhi’s aim, invest in diagnostics, modelling, and transparency rather than abstentions in UNGA voting over CTBT that telegraph appetite for thermonuclear validation. The region watches Pokhran, not just paragraphs.

Science, sensors, and stewardship are the backbone of the test-ban norm, and these must remain strong. But the canopy is thinning by a U.S. “No” at First Committee, India’s abstention, a contested presidential testing directive, Russia’s CTBT de-ratification, and conspicuous nuclear exercises cum new-system claims. This is how cascades begin from: talk → to preparations → and ultimately chain of tests. The stabilizing move is not to blink; it is to verify restraint faster than politics can erode it. That is what a Moratorium-Plus compact would do.

Author: Dr Zahir Kazmi (The author is Arms Control Advisor at the Strategic Plans Division and a former Brigadier. He can be reached through his X account, @Zahirhkazmi. The views expressed are solely his own)